|

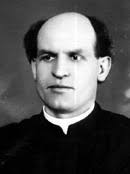

10/11/2023 0 Comments October 11th, 2023Accused of hiding Jews, Father Remigiusz Maria (born Antoni Wójcik) was arrested, tortured for three days by German Socialist Gestapo and murdered, on July 26, 1942, by two dogs, handled by Oskar Brandt.

0 Comments

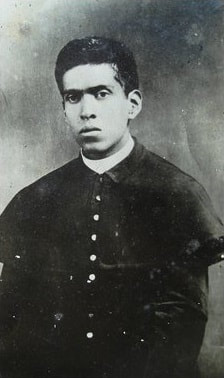

10/11/2023 0 Comments October 11th, 2023Benedicto Romero, Manuel Hernández, 17, Francisquillo Santillán, 14, executed behind the Cathedral of Colima, July 25, 1928. Victims of the Christophobic, Socialist Mexican regime.

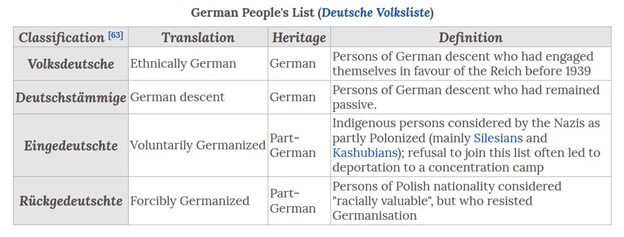

10/10/2023 0 Comments October 10th, 2023For his brave and vocal criticism of the German Socialists, Father Robert Wohlfeil was arrested on the very first day of World War II, the invasion of Poland, September 1, 1939. Beaten and tortured, he was shipped to Stutthof concentration camp, where he refused to sign the Volksliste, which could have released him from the camp. Transferred to Sachsenhausen concentration camp, he was tortured and then killed by camp kapo Fritz, who threw him off a roof.

10/10/2023 0 Comments October 10th, 2023As Padre José María Robles Hurtado prepared to offer Mass, which was illegal, the soldiers of the Socialist Mexican regime arrested him and dragged him to a barracks, where, at midnight, he was tied and forced to walk to Sierra de Quila, where at the highest point, soldiers stopped at a leafy oak tree.

Understanding he was to be hanged, the priest took the rope in his hands, blessed it and threw it around his neck, before the soldiers executed him, in the early morning hours of June 26, 1927. 10/8/2023 0 Comments October 08th, 2023Despite the German Socialist policy that relegated ethnic Poles as a second-class nation suitable only for slave labor, Sister Maria Wiśniewska secretly taught catechism and reading and writing, for which she was arrested.

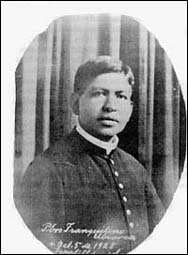

Dragged to the Gestapo headquarters, she was brutally tortured: her head looked scalped, her mouth deformed with broken teeth, lacerated lips and gums, and she could not stand because of broken bones. But she bravely bore her sufferings, singing hymns, praying continually, and never revealing anything. She perished shortly after, on November 19, 1943. 10/8/2023 0 Comments October 08th, 2023Before Padre Tranquilino Ubiarco Robles was executed, the general called one of the youngest soldiers to kill the priest. With trembling hands, the soldier held the shotgun pointed at the head of the priest and suddenly dropped it and started crying, saying over and over again, "l can not kill this man."

"If you don't do it, you are going to die along with him," the general threatened, on October 5, 1928. "Let it be it, then," answered the soldier. "But before you die, just tell me what is the reason why you would not kill this man." The young soldier answered, "Sir l cannot shoot this man, because he is my godfather and is the one who gave me the Sacrament of Baptism and the one who gave me my First Communion." And with that, the soldier was shot in the same spot, screaming, "Viva Cristo Rey! Viva Cristo Rey!" As told by Michael Gutierrez, whose very special father, David Gutierrez Polomino, a teenage witness at the time of the Mexican Cristero War, had told him. 10/5/2023 0 Comments October 05th, 2023German Socialists banished Seminarian Kazimierz Wilusz from his religious house in Struga, and killed him the next day, August 2, 1944, along with Brother Franciszek Janusz.

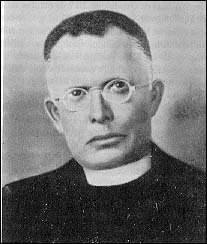

10/5/2023 0 Comments October 05th, 2023In defense of the Faith, clergy, religious and laity, many priests joined the fight during the persecution of the Catholic Church by the Mexican government, which caused the Cristero War.

One priest was Padre Miguel Pérez Aldape, a regimental chaplain, who defended the Holy Cause with his crucifx, a saddlebag with his vestment stole, and a 30-30 rifle. In the December 1928 photo are (L to R): Colonel Victor Lopez, General Miguel Hernandez, Colonel Toribio Valdez, Padre Miguel Perez Aldape, and Lieutenant Teniente Eulogio Gonzalez. Defending the Faith, Lieutenant Gonzalez was a sharpshooting sniper, an honorable man who humbly admitted that he shot more than 100 Federal soldiers, but much regretted leaving many families without a father, son, brother, husband. He married Maria Hernandez de Mendoza, cousin of General Miguel Hernandez. 10/4/2023 0 Comments October 04th, 2023Father Stanisław Wilk escaped the German Socialist roundups of clergy, October 5-7, 1941, but was later arrested and transported to Dachau death camp, where he perished, November 27, 1942.

10/4/2023 0 Comments October 04th, 2023An active member of Catholic Action David Roldán Lara was arrested, accused of conspiring to revolt against the government, beaten and tortured during the Cristero War during the persecution of the Catholic Church by the Mexican government.

Days later, at noon, on August 15, 1926, the Feast of the Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary, he was taken to a remote spot in the mountains and executed by a firing squad, after he shouted, "Long live Christ the King and Our Lady of Guadalupe!" 10/3/2023 0 Comments October 03rd, 2023After the German Socialists invaded Poland, they soon began the Intelligenzaktion, the campaign to exterminate ethnic Polish Catholic intellectuals.

Father Władysław Wilczyński was dragged from his rectory, beaten and tortured. Released, he was later arrested and shipped with a group of priests to Dachau death camp, where he was transported to Hartheim Euthanasia Center and executed in a gas chamber, June 11, 1942. 10/3/2023 0 Comments October 03rd, 2023Manuel Moralez, president of the National League for the Defense of Religious Liberty in Mexico during the Cristero War, was arrested a few days after a League meeting, during which he said, "The league should be peaceful and not interfere in political affairs. Our project is to implore the government to remove the articles of the Constitution that prevent religious freedom."

Imprisoned in the town hall, he was beaten and tortured, until August 15, when soldiers removed him from his cell and drove him to the mountains near Chalchihuites. Accused of conspiring to revolt against the government, he was brought forward with another who begged for Moralez's freedom, because he had children to support. Moralez said, "I am dying for God, and God will care for my children." And before his execution by firing squad, he hollered, "Long live Christ the King and Our Lady of Guadalupe!" 10/2/2023 0 Comments October 02nd, 2023Rounded up by German Socialists weeks after the invasion of Poland, Father Józef Wierzejski was forced to stand at the wall of the parish church in Mszczonów, where he was shot to death, as was the church vicar Father Władysław Gołędowski, November 9, 1939.

10/2/2023 0 Comments October 02nd, 2023"Here I am," said Salvador Lara Puente when the Mexican federal soldiers arrived to arrest him.

A member of the National League for Defense of Religious Liberty, an organization that defended Catholics against the persecution of Mexico's government during the Cristero War, he was arrested during one of its meetings. After driven to the mountains, he realized he was going to be executed, and he walked to the spot, praying in a low voice. Offered his life and his freedom in exchange for his recognition of the legitimacy of the anti-Catholic government, he refused and was shot on the spot, on August 15, 1926. 10/1/2023 0 Comments October 01st, 2023Because he was a Catholic monk, Brother Wacław Wilemski was arrested by German Socialists who barged into the Górka Klasztorna monastery. Transported to Paterek, he was executed with his two blood brothers, November 11, 1939.

10/1/2023 0 Comments October 01st, 2023Standing on the side of the road, Father Luis Batiz Sainz was given the opportunity to save his life.

The federal soldiers, armed with guns, told him all he had to do was acknowledge the legitimacy of the virulent anti-Catholic, Mexican government. The priest refused and was shot on the spot, on the Feast of the Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary, August 15, 1926, in the desolate mountains of Chalchihuites, Zacatecas. 9/30/2023 0 Comments September 30th, 2023Because he was a Catholic monk, Brother Paweł (born Alfons Wilemski) was arrested by German Socialists who barged into the Górka Klasztorna monastery. Transported to Paterek, he was executed with his two blood brothers, November 11, 1939.

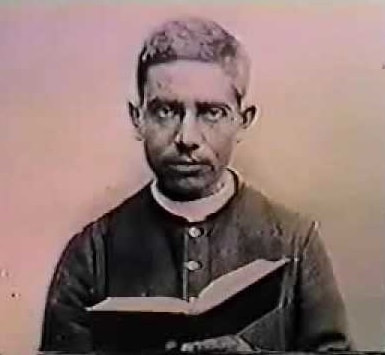

9/30/2023 0 Comments September 30th, 2023Facing the firing squad, in the Cemetery of Bethlehem, Father David Galvan Bermudez refused to be blindfolded and calmly pointed to his chest, where he would be shot, on January 30, 1915, the same day he was arrested for being a priest.

The Mexican government's anti-clerical stance had begun following the dethroning and execution of Emperor Maximillian, in 1867. 9/29/2023 0 Comments September 29th, 2023After the German Socialists took over the monastery in Górka Klasztorna and turned it into a concentration camp, Brother Dominik (born Konrad Wilemski) was transported to Paterek, where he was executed with his two blood brothers who were also monks, November 11, 1939.

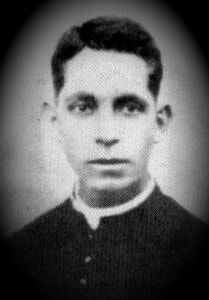

9/29/2023 0 Comments September 29th, 2023"I am innocent, and I die innocent. I forgive with all my heart those responsible for my death, and I ask God that the shedding of my blood serves toward the peace of our divided Mexico," said Father Cristóbal Magallanes Jara, as he faced his executioners and absolved them before they shot him to death, on May 25, 1927.

During the Cristero War, the Christian uprising against the oppressive anti-clerical Mexican government that persecuted Catholics, Father Cristóbal Magallanes Jara was arrested on his way to say Mass. For being a priest, he received a death sentence. 9/28/2023 0 Comments September 28th, 20232 top gates, Nazi camps --"Arbeit macht frei" (Labor makes free/liberates.)

2 bottom gates, Soviet camps -- "Labor in the USSR is a matter of honor, a matter of glory, valor & heroism" The difference? The 卐 had metal gates, and the ☭ had wooden gates. 9/28/2023 0 Comments September 28th, 2023"We live for God, and for Him we die," declared Father Agustín Caloca Cortés, his last words before executed by the firing squad, on May 25, 1927, in Colotlán, Jalisco, Mexico.

The 29-year-old priest was arrested by the anti-Catholic government, after he had warned seminarians to flee and hide from the approaching federal soldiers. Although offered his freedom, he refused unless freedom would also be granted to his fellow prisoner, Father Magallanes Jara, which was denied. 9/26/2023 0 Comments September 26th, 2023Only weeks after the German Socialists invaded Poland, they took over Górka Klasztorna monastery and converted it to a concentration camp. While being loaded into a truck, Brother Bolesław Wysocki tried to escape, but was fatally shot, November 11, 1939.

9/26/2023 0 Comments September 26th, 2023"Give us our temples, or we will take them!" protested Catholic faithful.

Churches were closed, the Sacraments outlawed and priests became enemies of the state after President Plutarco Elías Calles pushed a statute to enforce the anti-clerical articles of the Mexican Constitution of 1917, which sought to eliminate the power of the Catholic Church. The result was a civil uprising -- the Cristero War (1926–29). Countless faithful were martyred and 4,000 priests were martyred in or exiled from Mexico for offering the outlawed holy sacrifice of the Mass. 9/25/2023 0 Comments September 25th, 2023Falsely accused by German Socialists of haboring Wehrmacht deserters, Father Stanisław Wyszyński was sentenced to death and executed, as he stood barefoot, without a cassock, with his hands bound by a telephone wire, October 23, 1944, in the Kosówka Forest, Grajewo County.

|

AuthorTHERESA MARIE MOREAU is an award-winning reporter who covers Catholicism and Communism. Archives

October 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed