|

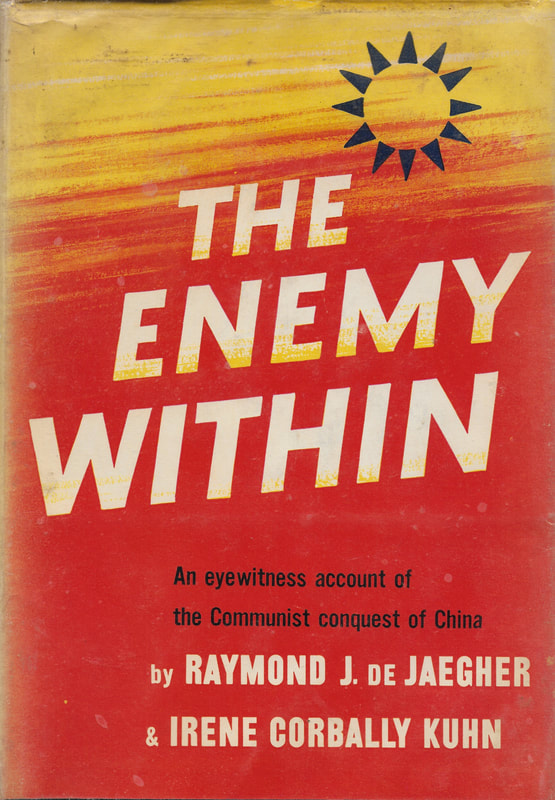

One day I was sorrowfully concluding my morning duties in Ch’en Lu Che, one of the parishes under my care, whose priest had been arrested by the Reds. The big bell in the village sounded, and a frightened youth, who had been the priest’s servant, came to tell me that the Communists had issued orders through the mayor to everyone in the village to assemble at an open place ordinarily used as a children’s playground. “You will have to go too, Father,” the young man said. “Everybody must be there at 10 o’clock.” The bell sounded again and its heavy, ominous peals depressed me even more. I questioned the boy, but he was too terrified to talk, so I decided to go along and see for myself what the Communists were up to now. When I reached the playground, I found the whole village assembled there, old and young, men, women and children. The children, with their teachers, were in the front row. I inquired what we had been brought here for, and one man whispered to me: “We are to witness an execution – a beheading.” His companion leaned over my shoulder and spoke in low tones behind his hand. “It is a big execution. They say there are many – 10 or more.” “What is their crime?” I asked. “They have committed no crime,” the man said with bitterness. “They are students. From the anti-Communist school in Chang Ts’un.” “Yes, that is right,” the man answered. Then he pulled my arm. “Look, here they come! And see – the children! These beasts will make the children witness this horror!” The man shuddered, then spat violently on the ground in anger and disgust. Memories came flooding of my young friend, Wang Chi-sien, a graduate of this school, buried alive when the Communists were systematically tracking down all its graduates. I prayed for strength; I reminded myself that I must be the coldly objective surgeon; I must no let my feelings and emotions overcome me. I must watch and observe and not let these Red devils prowling around up and down the lines of people suspect that I was sick with revulsion already. The man behind me had said, “Here they come.” I looked now and saw that a file of young men, most of them in peasant dress, hands bound behind them, were being led into the cleared space. They were all so young, so very young! A Communist soldier barked orders at them, and they were all obliged to kneel down facing the people. The Communist barked more orders, and the young men moved closer to each other on their knees until they were not more than a foot apart. I counted them. Thirteen of them knelt there in the brightness of the morning, the wind from the northern plains blowing across their young faces. These were the fine youth of China, the good, incorruptible ones, and they were going to be liquidated because they were incorruptible. The local militia, which had been guarding them, stepped back. A Communist officer read out a long rigmarole of charges against them. The word “traitor” kept jumping out of his mouth. The people were silent. Contempt was written on their faces. Everyone knew these young men and knew they were not traitors. The Seu-Tsuen School was a most democratic one. Its principal had conceived the idea of a half day of studies and a half day of agricultural work, a kind of practical training in new methods so that the students who couldn’t go outside their province for an education would at least have some knowledge and be able to read and write a little when they had to return to their fathers’ farms. It had made wonderful strides in giving a little education to peasant youths who otherwise would have been entirely unlettered. Given time, it could have leavened all of the largely illiterate are with knowledge. The people listening to the trumped-up charges knew, too, that even if these young men had wanted to be traitors they could have had no opportunity since there were no Japanese in the area. With this curious sense they have of knowing just when to stop their tirades and diatribes and strike, the Communist leader now gave two orders simultaneously: He told the teachers, white and trembling already, to start the children singing patriotic songs. And he gave the signal for the execution to the swordsman, a tough, compact-bodied young soldier of great strength. The soldier came up behind the first young victim now, lifted his great, sharp, two-handed sword and brought the blade down cleanly. The first head rolled over and over, and the crowd watched the bright blood spurt up like a fountain. The children’s voices, on the thin edge of hysteria, rose in a squeaky cacophony of dissonance and garbled words; the teachers tried to beat time and bring order into the tumult of sound. Over it all I heard the big bell tolling again. Moving as quick as light from right to left as we watched him, the swordsman went down the line, beheading each kneeling student with one swift stroke, moving from one to the next without ever looking to see the clean efficiency of his blow. Thirteen times he lifted that heavy sword in his two hands. Thirteen times the sun glinted off the blade, dazzlingly at first, then dully as the red blood flowed down over the shining steel and stained and dimmed its glow. Thirteen times the executioner felt steel pierce cartilage and flesh, slide between two small neck bones. Not once did he miss. Not once did he look back at what he had done. And when he came to the thirteenth, the last man, and had chopped his head off, he threw the sword down on the ground and walked away without looking back. I thought sardonically as I saw this through my own misted eyes that, inhuman devil that he was, he still believed in the ancient Chinese superstition that if a killer looks on the man he has killed at the instant of his death, the soul of the victim, escaping from the body the instant the head is severed, will rush into the soul of the killer, who never afterward in all his lifetime will know a moment's peace. The cautious Communist was taking no chances; this is why he had beheaded the men almost without looking at them. There were a few Chinese in that company of forced watchers who now rushed forward with piece of man tow, the steamed bread of North China, to dip them into the blood gushing from the trunks of the beheaded youths. Some chinese believe that if one has ye che – a weakness in the stomach – eating bread soaked in blood will strengthen the organ and cure the disease. Criminals were always beheaded in China in the old days and in modern times too, but it was rare for any Chinese to avail himself of the opportunity to test the gruesome remedy. The Communists, however, encourage the people in revolting superstitions like this. On this day, though, they didn't indulge them long. They had something they wanted to do themselves. My eyes started from my head when I saw what the Communist soldiers did next. Several of the strongest, most aggressive among the group rushed forward now and pushed the corpses over on their backs. I stared horrified as each soldier bent down with a sharp knife and made a quick, circular incision in the chest. He then jumped on the abdomen with both feet, or pumped on it over and over with one foot, forcing the heart out of the incision. Then he swooped down again, snipped and plucked it out. When they had collected the thirteen hearts, they strung them all on a pointed marsh reed, flexible and resilient, which they tied together to make a hand circular carrying device. The two villagers who had watched all this, too, turned looks of withering scorn on the departing Communists. “Why did they do that terrible thing?” asked the older one. “They will eat the hearts tonight. They believe it will give them great strength.” And he turned away and cursed them violently. “Look at the children,” sighed the other. “Our poor children!” he said, shaking his head sadly. The youngest were pale and disturbed. A few of them were vomiting. The teachers were scolding them and getting them together now to march them back to school. This was the first time I had seen small children forced to watch such bloody executions. It was all part of the Communist plan to harden and toughen them, make them callous to acts of barbarous cruelty like this, and terrify them with Communist power. Unhappily, it worked in many cases. After this I often saw children forced to witness executions. The first time they were horror-stricken and emotionally disturbed, often sick at their stomachs as these children were. The second time they were less disturbed, and the third time many of them watched the grisly show with keen interest. The second ringing of the bell for the execution of the 13 students of Seu-tsuen School was at 10 o’clock. The beheadings took about 10 minutes. It was all over in less than half an hour, the violation of corpses, the return of the children to school, the sad departure of the families of the young men with their desecrated bodies, and the dispersal of the crowds. Communism is most efficient. ------- by Raymond J. de Jaegher, from “The Enemy Within: An Eyewitness Account of the Communist Conquest of China”

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorTHERESA MARIE MOREAU is an award-winning reporter who covers Catholicism and Communism. Archives

October 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed