|

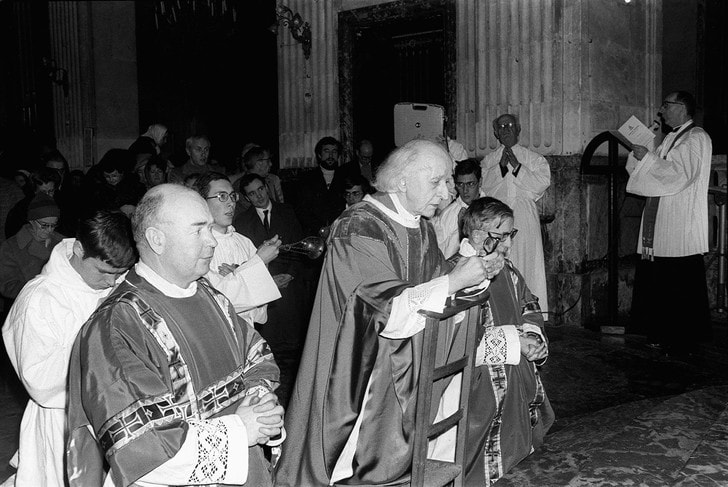

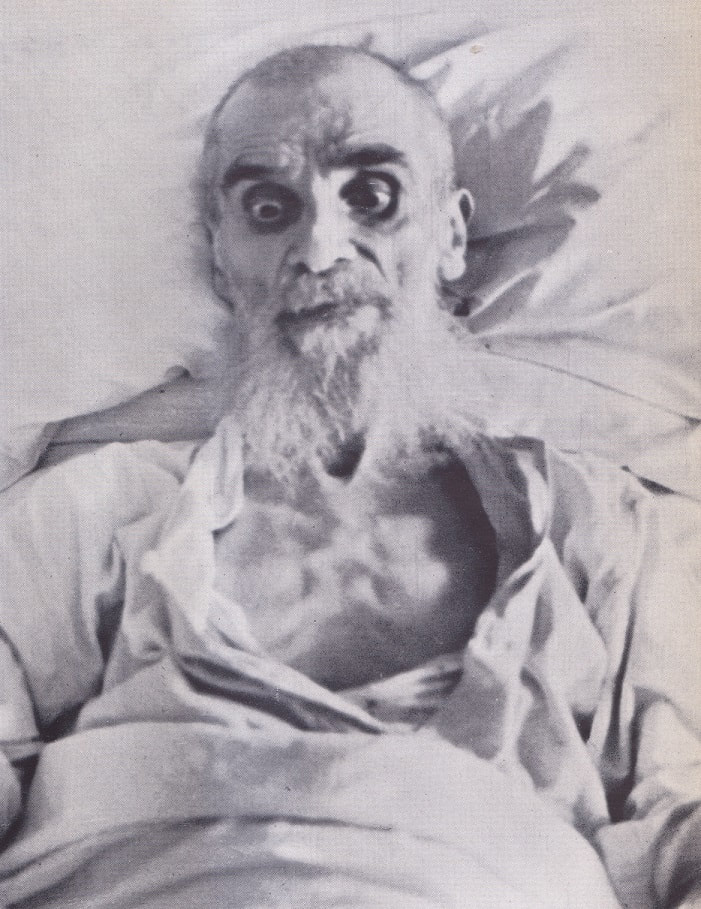

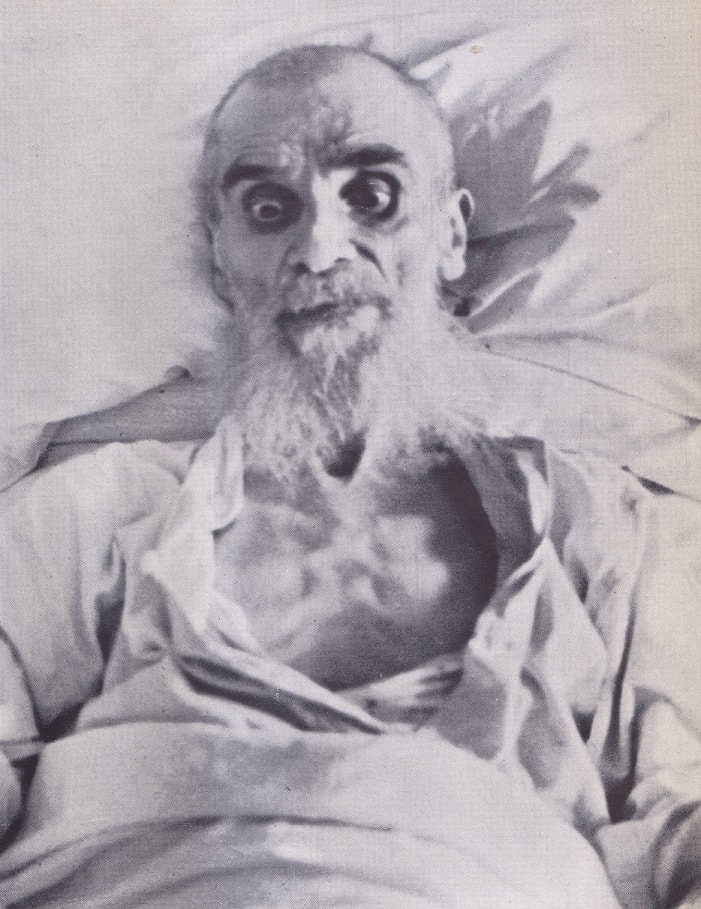

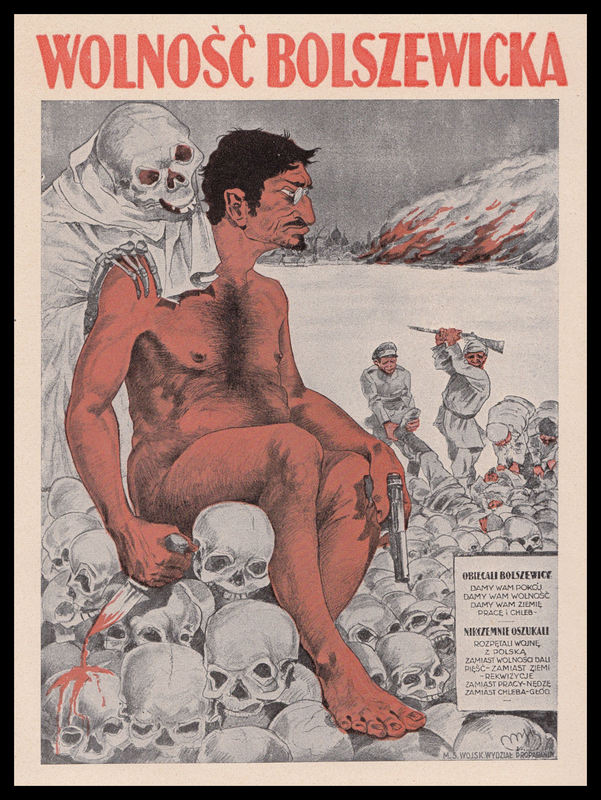

9/21/2017 0 Comments SAINT NICOLAS DU CHARDONNET, first published in Catholic Family News, December 2005RECAPTURED PARIS CHURCH PRESERVES TRUE MASS By Theresa Marie Moreau First Published in Catholic Family News, December 2005 ---- A single tap of a priest’s knuckle upon the blackened mahogany arm of a choir chair signals the morning’s recitation of the Divine Office. The Roman-collared men gathered in the sanctuary of St. Nicolas du Chardonnet de Paris raise the breviaries they hold in their hands and flip the thin pages until each finds the day’s prayers. “Deus, in adjutórium meum inténde (O God, come to my assistance),” the church’s pastor, seated on the Gospel side of the altar, chants in a rich voice. From the Epistle side, four priests respond, “Dómine, ad adjuvándum me festína (O Lord, make haste to help me).” Their prayers rise. In the nave, a baker’s dozen of parishioners—some kneeling, others sitting—assist with their own prayers, in silence. For the next fifteen minutes, the men, dressed in the ankle-length, death-black cassocks appeal to God. They stand. They bow. They nod. They cross themselves in pious affirmations, as the first rays from the morning’s sun seep through the stained-glass depiction of the Crucifixion, two stories overheard. Although Catholic churches held rites like these for centuries, St. Nicolas du Chardonnet is no ordinary church. Freed from the diocesan bishop’s strangulating jurisdiction of the post-Second Vatican Council’s “new-and-improved” Roman Catholic Church, St. Nicolas, located at 23 rue des Bernardins in Paris, is one of a few churches in secular France that regularly and exclusively offers the traditional Latin-rite Mass. It all began in 1977. In Paris at that time, there was one old priest who clung to the Tridentine Mass of Pope St. Pius V, codified on July 14, 1570 following the Council of Trent (1545-63). The old religious Frenchman refused to go along with the progressives, the priests who experimented with innovations tossed into the Novus Ordo Missae (the New Order of the Mass). That man was the Rev. François Ducaud-Bourget, ordained in 1934. A bit on the short side, he stood slightly hunched over, with a hook nose that protruded from the center of his small face flanked by long tufts of white hair covering his ears. At times he pointed his crooked finger through the air to emphasize certain points in his sermons, always delivered with traditional instruction on morals and doctrine. He never went the way of the post-Vatican II folksy style of the self-reflective, feel-good homily commonly punctuated with jokes to keep the parishioners happy—and awake. He wouldn’t degrade himself, or his office, in that way. Even though Pope Paul VI had signed the Apostolic Constitution Missale Romanum on April 3, 1969, thereby handing the Church a reformed Missal, Ducaud-Bourget disdained the man-centered modernizations. He kept his back to parishioners. He continued to face the altar and to pray the ancient rite. As those before him, he began in the beginning with Psalm 42, a preparation for the sacrifice of the Mass, and ended with the emotionally inspiring Last Gospel. “He never said the New Mass. Never,” says Monsieur l’abbé (the Rev.) Bernard Lorber, of the Fraternité Sacerdotale Saint-Pie X (the Society of St. Pius X) and the premier vicaire of St. Nicolas. Best described as a priest independent from the diocese, in the ’70s Ducaud-Bourget frequently rented a meeting place where he could offer the Latin Mass for the community. Sometimes he paid for a room in the La Salle Wagram, a banquet hall near the Arc de Triomphe, at other times a room in Maubert Mutalité Lecture Hall, a building very near St. Nicolas du Chardonnet. But on February 27, 1977, Ducaud-Bourget had a plan. When traditionalists met at Maubert that Sunday, the old priest led everyone across the street to St. Nicolas, which suffered greatly from the chronic Novus Ordo syndrome: spiritual neglect. From 1968 to 1977, diocesan priests from the parish church, St. Severin, located a few blocks away, only opened the doors of St. Nicolas for a single new Mass once a week. Usually, only a handful of parishioners bothered to show up. Ducaud-Bourget hoped to inject some supernatural powers of Jesus, Mary and Joseph back into the church, thereby inoculating it against the fatalistic forces of humanistic relativism. He had no idea how successful he would be. “It was his intention to say the Mass here on this Sunday, then to pray during the day and then to leave the place after,” Lorber says. “But there were so many people, they thought they would stay one more day, then one more day, then one more day, then one more day. Eventually, they decided to stay here, to remain here forever.” There was only one problem: The occupation was illegal. Even though the diocesan bishop of Paris was deemed the caretaker for the property at the time, it was (and still is) the state of France that owns every church built in that nation before 1905. Going back a few years, in 1905, the Law of Separation of the Churches and the State (Loi de Séparation des Eglises et de L’Etat) made it official that the state of France no longer recognized the Roman Catholic Church, but only distinct associations cultuelles (associations for worship), ordered established in each parish. Where no associations formed, the state declared it would take possession of the church property. From his seat in the Vatican, Pope Pius X looked toward France and feared spiritual demoralization: state intervention in religious parish life. To take a firm stance against the meddling modernists, the Vicar of Christ, in his 1906 encyclical “Gravissimo oficii,” forbade the formation of any associations cultuelles. Thus, Rome forfeited property for principle. “The Church lost everything,” says the Rev. Thierry Gaudray, 38-year-old professor of Dogmatic Theology at St. Thomas Aquinas Seminary, in Winona, Minnesota. “Police entered the churches with guns. They opened the tabernacles. They forced out of the churches and onto the street the priests and nuns,” Gaudray describes. Everything the Church had gained with the Concordat of 1801, it lost in 1905. Not only had the nineteenth-century agreement between Napoleon Bonaparte and Pope Pius VII officially raised the recognition of Catholicism as the religion of the majority of French citizens, but it also stipulated that the state would financially support the clergy, which it did. Although one hundred years ago the Church lost its spot in France’s secular pecking order, it wasn’t a total loser, exactly. For when the state took custody of church property, at least it allowed bishops to remain in charge of the churches. With one single stipulation: In every church, one Mass was to be said each year. If not, the state would retake control of the sacred structure and do with it what it wanted. “So, St. Nicolas was part of the diocese of Paris, and the bishop of Paris was in charge of the building, but the state did own it,” Gaudray clarifies. “Ducaud-Bourget took the church against the will of the bishop, which was illegal. Taking over a church, to enter a church and to take over, it is illegal.” The state did decide to take legal action, but only after Ducaud-Bourget and his army of Church Militants had entrenched themselves deep in their sacred battlefield. For even on the first night when Ducaud-Bourget and the others entered St. Nicolas, they had adoration of the Blessed Sacrament. That lasted for the entire first week. What could officials do against a bunch of pacifist worshipers? “The police could do nothing, because the people prayed,” Lorber says. Months following St. Nicolas’ liberation from the Conciliar Church, the state indeed tried Ducaud-Bourget and issued a decree of expulsion. However, officials never executed the judgment. It’s now 2005, twenty-eight years later, and traditionalists continue to occupy St. Nicolas. Seated in the same sacristy where Ducaud-Borget sat, Lorber looks toward the altar as he tries to explain the state’s inaction. “Every Sunday, Monseigneur had 5,000 people here in St. Nicolas, and if they were forced to leave this church, they would just go to another church and takeover that one. Officials understood it would be the same problem, so they understood it was best to keep silent about our action. So they decided to do nothing, to leave us here.” And even if the diocese wanted to take back St. Nicolas, on principle, it wouldn’t work, Lorber says. The diocese wouldn’t be able to occupy all the churches. They don’t have enough faithful who attend Mass. Although a reported eighty-five percent of the 60.4 million French claims to be Roman Catholic, it is uncertain how many regularly go to church on Sunday. For a time, Ducaud-Bourget took care of the church, but he was already old. Desperate to continue the traditional efforts he resurrected in St. Nicolas, he sought help from one of the most vociferous defenders of the Tridentine Mass: Archbishop Marcel Lefebvre, who in 1969 founded the Society of St. Pius X, an order dedicated to the training of priests in the rites of the ancient Church, pre-Second Vatican Council style. Lefebvre aided Ducaud-Bourget and dispatched one of the Society’s priests to help the elderly man. Despite the leadership he demonstrated in his part to keep the old Mass alive, Lefebvre has had his detractors. Or maybe it was because of his leadership. Through the years, critics of the archbishop have accused him of being a religious Pied Piper responsible for leading a whole legion of Catholics into excommunication. That often-repeated description is absolutely not accurate, snaps Lorber, who explains that Lefebvre was already settled into retirement in 1968 when several young seminarians visited him. Unhappy with the Conciliar Church, they approached him and begged him to teach them the traditions of the faith, to pass on what he, himself, had learned. “The seminarians went to him and asked him why had did not found a seminary. He did not want to,” Lorber says. “I am an old man,” Lefebvre told them and sent the young men to a seminary in Fribourg, Switzerland. However, the modernistic teachings in that religious school were no better than any other seminary. The following year, the desperate seminarians and priests returned and insisted the archbishop establish a seminary where novitiates could learn the ancient-yet-solid foundations of the faith, including the Tridentine Mass. Lefebvre acquiesced. Meanwhile, in Paris, Ducaud-Bourget continued the occupation of St. Nicolas until his death in 1984. Subsequently, his body was interred behind the main altar, where he had offered the old Mass every day in the last years of his life. After the old priest’s death, Lefebvre sent two more priests from the Society to the Parisian church. Ducaud-Bourget’s dream would not die with him. Sticklers to tradition, like those in the Society, made the hierarchy in Rome cringe. Since the adoption of the vernacular rite in 1969, the Vatican found it had to deal with the holdovers who preferred the Latin Mass and refused to offer or even attend the new Mass, claiming it was a Protestantized fabrication. Only a couple years into his pontificate, Pope John Paul II established a nine-cardinal commission at the Vatican to study the Mass problem. On October 3, 1984, the Congregation for Divine Worship issued its circular letter, “Quattor Abhinc Annos.” This document describes the granting of and the restrictions placed on what is now commonly referred to as the Indult Mass. Indult, from the Latin indulgere (to indulge), is a privilege granted by the pope to bishops and others to do an action that the law of the Church otherwise prohibits. Yet the term “Indult” is misplaced, since the Latin Tridentine Mass has never been prohibited, which Alfons Maria Cardinal Stickler—one of the nine cardinals on the commission—admitted in May 1995 while speaking at a ChristiFideles conference held in New Jersey. Stipulations in the 1984 “Indult” included that the Mass only be offered (definitely not in parish churches) to those who request it, and those parishioners could in no way share the beliefs of those who question and doubt the validity of the new Mass. Meanwhile, the Society of St. Pius X continued to flourish and continued to offer the old Mass, not only at St. Nicolas, but also at other churches around the world. Lorber, now 41 years old, has witnessed much of the Society’s growth, despite the hardships the traditionalist order has had to endure at the manipulative hands of the hierarchy. Ordained on June 29, 1988, Lorber was one of the last to have his hands consecrated by Lefebvre, who died in 1991. A few weeks before his ordination, Lorber served the low Mass for the archbishop in the Notre Dame des Champs Chapel in the Seminary of Ecône on May 8, a Sunday. Lefebvre told Lorber how during the month before, in April 1988, he went to Rome to discuss with the Vatican the impending consecration of the bishops he had planned to take his place for the administering of sacraments, the ordaining of priests and the confirming of the faithful. Born in 1905, the archbishop was old and did not want to leave his priests without a spiritual leader. The Vatican’s representative at that time was Joseph Ratzinger, then a cardinal and now Pope Benedict XVI. In the end, after lengthy discussions and many compromises, a protocol was signed on May 5, 1988. The agreement stipulated that Rome would give Lefebvre one bishop and a commission in Rome to discuss the traditional Mass. “Ratzinger was quite hard with Archbishop Lefebvre,” Lorber says. After Lefebvre signed the protocol, he told Ratzinger that he had already announced the episcopal consecrations for the following June 30. Ratzinger’s response: No. It’s not possible. August? asked Lefebvre. No. It’s not possible, Ratzinger responded. November? No. December? No. Lefebvre left Rome and sought solace at the Seminary of Ecône, in Switzerland. He prayed. On May 6, he wrote to the Vatican and expressed that he did not have confidence in the agreement. “During the discussions with Rome, it was very painful,” Lefebvre told Lorber, “It was very painful, because they don’t take care of their souls. The only one thing they try to do is save their image, and this is why I will consecrate the bishops without Rome.” But the Vatican continued to pressure the archbishop. “The day before the consecrations, Rome sent a messenger, a nuncio from Switzerland, to take Archbishop Lefebvre back with him. The Pope asked if he could go to Rome to talk with him. The seminarians told him it was a good joke,” Lorber says. “The intention was to make Lefebvre nervous about the consecrations, but it didn’t disturb Archbishop Lefebvre.” Nothing bothered him. Not even the rumors circulating that he would be “excommunicated” if he went ahead with his plans for June 30. As for the excommunication of bishops, there were precedents. Decades earlier, in the 1950s, Pope Pius XII introduced into Canon Law, the prohibition of bishops consecrating bishops without papal approval. The Pope found this necessary after the Communist takeover in China. That was when the faithful of the Roman Catholic Church (the Underground Chinese Catholics) in China found themselves persecuted after the rise of the Chinese Patriotic Church (the pseudo-religious association that collaborated with the Chinese Communist government), explains Gaudray. “The law of the Church is for the good of the souls, so when Pius XII issued the decree of excommunication for the bishops in China, it was for the good of the Church. It was to prevent the setting up of the national church in China, which is not Catholic. It was to make people aware that the Pope does not agree at all and for them not to be part of the schismatic church,” Gaudray says. “The purpose of Archbishop Lefebvre was not to form another Church. Our bishops do not have authority, even in the Society. We have bishops for the sacraments, ordinations and confirmations. In China it was to form a Church.” The day finally arrived. Lefebvre predicted in his sermon before the consecrations there would be an attempt to excommunicate him. Nonetheless, on June 30, without papal permission, Lefebvre consecrated four bishops: Bernard Fellay, Bernard Tissier de Mallerais, Richard Williamson and Alfonso de Galarreta. “Many realized that the consecrations was an historic event for the Church,” Lorber says. It was a matter of preservation, not of the self, but of the faith. As predicted, on July 1, 1988, the Vatican, represented by Bernardinus Cardinal Gantin, prefect of the Congregation of Bishops, issued the following: “I declare that the above-mentioned Monsignor Marcel Lefebvre, and Bernard Fellay, Bernard Tissier de Mallerais, Richard Williamson and Alfonso de Galarreta have incurred ipso facto excommunication latae sententiae reserved to the Apostolic See.” This was accompanied by even more threats. “The priests and faithful are warned not to support the schism of Monsignor Lefebvre, otherwise they shall incur ipso facto the very grave penalty of excommunication.” Excommunication, explains Gaudray from his office in Winona, is a severe technical punishment issued by the Pope that severs all ties between the chastised and the Church. Penalized priests cannot give or receive the sacraments. They cannot offer or even attend Mass (new or old). “This, of course, means it is a punishment, but it implies a fault, that something is wrong,” Gaudray says. Both Gaudray and Lorber claim the excommunication was unjustified. For, they believe, Lefebvre committed no wrongdoing. “This excommunication has no value, really,” Lorber says. “Because for there to be punishment, one must have done something wrong. Archbishop Lefebvre didn’t have any schismatic intention by consecrating the bishops. His act was never a wrong, and he should never have been punished. Furthermore, by excommunicating Archbishop Lefebvre, Rome lost its credibility, because it lets bishops and theologians, like Hans Küng, Leonardo Boff and all the liberal theologians run around and teach heresies, and they were never excommunicated by John Paul II.” Lefebvre only tried to keep the old Mass, and the true Catholic religion, alive. “Without the actions of Archbishop Lefebvre, there would not be anymore priests who could say the Tridentine Mass,” Lorber says. Thus, the traditional priests of St. Nicolas continue the ancient rites of the one, holy, catholic, apostolic Church they learned from the old archbishop, coaxed out of retirement, reluctantly. Still, every morning, a single tap of a priest’s knuckle upon the blackened mahogany arm of a choir chair signals the morning’s recitation of the Divine Office. The Roman-collared men gathered in the sanctuary of St. Nicolas du Chardonnet de Paris raise the breviaries they hold in their hands and flip the thin pages until each finds the day’s prayers. “Deus, in adjutórium meum inténde,” chants one, followed by the others responding, “Dómine, ad adjuvándum me festína.”

0 Comments