|

Persecution and anti-Catholic propaganda By Theresa Marie Moreau First published in the Remnant Newspaper, November 30, 2017 As long as you did it to one of these my least brethren, you did it to me. – Matthew 25:40 – REPORTER’S NOTE: For the past several years, as attacks against the Catholic Church have accelerated in an increasingly Socialist world, news sources have published and broadcast sensationalized pieces about dead babies interred in underground chambers on Catholic estates, including Bon Secours Mother and Baby Home, in Tuam, Ireland, and Smyllum Park Orphanage, in Lanark, Scotland. With anti-Catholic verbiage, reporters ran with the pieces – seemingly, never letting facts get in the way of a good story – maligning priests and nuns with vicious tales and innuendo of abuse and torture, elaborated and hyperbolized with words such as horror, notorious, gruesome, grim and brutal. But in the reports, there was something eerily familiar. Similar accounts can be found in the historical works that fill volumes of aging, yellowing pages pulled from the shelves. For more than 60 years ago, the same sort of false accusations were launched against Catholic missionaries in the People’s Republic of China after the Communist takeover. Here’s what happened: ††† Babies. Syphilitic, illegitimate, deformed, unwanted, diseased, blind. Abandoned. Tossed aside in alleyways of China’s cities, along dirt ways of lonely villages, atop dunes of dust on windy stretches of desert, among rock-filled passageways atop mountains, amid empty tombs of silent cemeteries. Murdered. Dumped in the trash, laid out for wild dogs, flung into rivers, dropped down wells, suffocated with vinegar-soaked paper, starved, buried alive. That was the macabre life and death that greeted Catholic missionaries upon their arrival in mainland China during the first half of the 20th century, when their callings put into practice Christ’s Second Great Commandment: Love thy neighbor as thyself – a supranational, supernatural compassion for all God’s creatures. In Oriental villages and cities, Occidental women in flowing veils and habits opened orphanages and dispensaries to accommodate a desperate need, to comfort, aid and protect the smallest and weakest victims of human neglect and cruelty: abandoned babies. Countless infants, mostly girls, arrived at the missions. Some found alive by strangers, sometimes policemen. Some delivered in the dark of night at the doorstep or dropped into a basket left outside for such bundles. Some rescued by elderly parishioners, who received a few cents for each baby found during daily searches of garbage heaps, water fronts and dark corners. Too few rescued before it was too late, most never survived the rough starts in their innocent lives. Too sick. Too chewed up. Too malnourished. Too beyond life. Most, more than 70 percent, arrived at the foundling homes dead or near dead. Heeding charity, the religious did the best they could in the worst possible circumstances. With the little, helpless bodies in their arms, believing in the immortality of the soul, the nuns baptized the dying, in their Angelic work. For the dead, a final solace, a respectful burial for a disrespected soul. In the mission’s private, Catholic cemetery, a common grave was set aside for the many interments of the many dead babies. In addition to the arrivals, day in and day out, the selfless nuns – under constant stress, with stretched resources and nerves, battered psychologically and scarred emotionally – battled the ever-present threat of deadly diseases and infections, such as measles, whooping cough, small pox, polio, tuberculosis, influenza, pneumonia and pleurisy, among others, which stole countless lives. Fortunately, some survived and even thrived. In 1949, 254 Catholic orphanages throughout mainland China cared for as many as 15,698 discarded children. But that was before the regime of the Communist Party seized control of the country. When the Reds grabbed the whip of power, in 1949, they promised freedom of religion and protection of foreigners’ property; however, as new masters, they methodically began a nationwide inventory, with constant updating, in all spheres of the society over which they ruled. They wanted a thorough accounting, for under Communist rule everything and everyone is controlled by, if not owned by, the People’s Government. For the first year or so, regime toadies visited each house, business and institution, wrote extensive notes and detailed lists of property and of persons: foreign and domestic, landowner and peasant, bourgeois and worker, counterrevolutionary and revolutionary. When completed, depending on the area, authorities set into motion their control over the population and possessions. Following the purges of their political enemies to instill fear into the masses, the regime began to implement the redistribution of wealth, of which a great deal slipped into their own Party pockets. The Communists wanted all private real estate and all valuable personal property to go to the State, the People’s Government, which was in charge of and in control of production and distribution. Here are just a few of the mandates: All institutions run by foreigners were to appoint Chinese directors, by December 17, 1950; All organizations receiving funds from the United States of America, considered imperialistic foreign devils, were to be taken over by the Chinese Central Relief Association, as decreed by the National State Council of Communist China, on December 29, 1950; All landowners, Chinese or foreign, who were to send titles and deeds to the People’s Government, no later than February 6, 1951; All businesses and institutions controlled directly by foreigners, were charged excessive taxation and forced overreaching regulations, to ensure a quick, inevitable insolvency; And for all others, the authorities seized by another type of coercion: In a by-force policy of fear and intimidation, they charged landowners with trumped-up crimes, distorted to dispossess land and possessions from the possessors. Victims found themselves under attack, with false accusations exaggerated in the state-owned-and-operated media for propaganda purposes. Those who ran Catholic orphanages found themselves under attack. ††† After the Communists moved into and took control of Canton (old form of Guangzhou), the capital of the province of Kwangtung (old form of Guangdong), they paid an official visit, on the morning of January 26, 1951, to the Society of the Missionary Sisters of the Immaculate Conception – to serve a search warrant. Everyone was ordered to stay put and not move, as the soldiers posted sentries at the exits, to make certain that no one escaped. While some of the soldiers went through every inch of the mission, more than a dozen others questioned orphans, trying to coerce them to accuse the Sisters of cruelty. “Admit that the Sisters maltreated you,” a soldier demanded. “The Sisters are our mothers. They love us more than did our own parents who abandoned us. We love the Sisters with all our hearts,” the children said. “Shame on you, children! Why do you love these foreign wretches who came over here to kill the children and steal our money? They pretend that they came to China to do good to the people, but they are hypocrites who cover themselves with the mask of charity.” “The Sisters rescued us when our parents no longer had any use for us. We love the Sisters. They are kind and gentle. We do not want them to be taken away from us!” In the afternoon, with the Communist soldiers still at the mission, a local woman arrived to surrender her baby, then another arrived and then another and another throughout the rest of the day: a 5-day-old girl convulsing from tetanus; a crippled premature baby girl; a 6-month-old suffering from pneumonia that followed complications from a bout of measles; a sickly, underdeveloped infant; and a newborn with green pus oozing from the remains of the umbilical cord cut in unsanitary conditions. The soldiers in charge grimaced and cringed at the sight of the sick and dying babies. “When are you leaving?” asked one of the soldiers. “Leaving for where?” asked one of the nuns, Sister Saint-Victor. “For your own country, of course.” “We are not leaving. The orphans are our children; without us, they would be quite helpless, so we have decided to stay.” At 6:30 that evening, the soldiers had Sister Superior Saint-Alphonse-du-Rédempteur and her assistant, Sister Sainte-Marie-Germaine, sign documents that nothing had been ransacked or robbed during the search; however, the men did take away with them the account books, the baptismal register and a record of the children likely to survive. But before leaving, authorities demanded and received an accounting of the number of daily receptions of babies, how they were brought to the orphanage, the tally of daily deaths and the manner of burials. According to the nuns’ notes, between October 14, 1949 (the day the Communists took over Canton) and January 10, 1951, the orphanage received 2,651 children, all who had been abandoned and left to die, many dropped along the roadside by refugees fleeing the mainland and its regime. The babies who did not survive were laid in, what was believed to be their final resting place, a common grave in the cemetery, sprinkled with quicklime, as required by law, and then a huge slab of stone was slid over the top. Although 2,116 had died, 535 survived in the mission settled, in 1909, by the Society of the Missionary Sisters of the Immaculate Conception, a religious order founded on June 3, 1902, in Notre-Dame-des-Neiges, Montreal, Canada. Running on funds supplied from their North American headquarters, as well as charity fundraisers and donations, the Sisters eventually established the Sacred Heart Orphanage, the Holy Infant Foundling Home, two schools and a leprosarium, with two freshwater wells and electricity. Situated outside the city, the mission’s buildings, with the crèche atop a small hill, were spacious and well-ventilated with large windows, all made possible with philanthropic gifts from Boon-Haw Aw (1882-1954), renowned as the Tiger Balm King. All children had their own beds, all babies had their own cribs and all slept covered with their own mosquito netting. With 60 babies below 1 year old, 33 between the ages of 2 and 5, and 34 between 5 and 18, to ensure all infants had proper attentive care, the nuns set up a system where eight of the older teenage girls were designated as little mothers. Each took care of a brood of five babies. At the end of World War II, when aid was being distributed by the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration, Western doctors and nurses thoroughly inspected the grounds and commended the nuns on their efficiency and the overall cleanliness of the facilities. The kitchen was spotless, and all formula and bottles were sterilized. After the Communists had completed their investigation, the nuns asked if they should continue their work. Not only were they praised for their service, but they were encouraged to go on as before. So the nuns resumed their daily duties, as permitted and urged by authorities. However, subsequently, each of the orphans was ordered to police headquarters, where they were photographed for official records and questioned endlessly while authorities tried, unsuccessfully, to coerce the children to make accusations against the Sisters. And then on February 7, 1951, the Sisters found themselves under attack in the newspapers. The Communists accused the women of being responsible for all 2,116 deaths of the babies, even those who had arrived at death’s door. The first attack was followed by another, on February 28, 1951, when the regime’s newspapers published an editorial that eviscerated the Sisters. In part, it read: “This orphanage, opened in 1933 with money from international Catholic organizations, symbolizes the hypocrite mask of the imperialists in their consistent plot of waging aggression under the pretext of charity work. Let’s deliver our next generation from the hand of those swindlers who have charitable faces and snake-like hearts!” The anti-Catholic propaganda editorial agitated the masses. Newspapers printed letters, supposedly from outraged readers who demanded that authorities investigate and punish the imperialists. Alongside the letters ran lurid newspaper stories with exaggerated accounts that were more fiction than fact: that the nuns lived in luxury, that the orphans were treated less than human, that the Sisters plucked eyeballs from the orphans to make traditional Chinese medicine, and that the orphanages were slaughterhouses. On March 1, 1951, at 2 in the afternoon, as part of the orchestrated theatrics of outrage, about 30 officers entered the mission and summoned Lo-Sail Chan, one of the older orphans, who had been entrusted with the management of the orphanage after the People’s Government decreed that institutions run by foreigners must appoint Chinese directors. “I am responsible for everything here, not the Sisters,” Lo-Sail said. “As far as the direction and administration of the house goes, well and good, as to the great number of dead infants, the Sisters alone are responsible,” the soldier said. One of the officers stood in the orphanage and read a formal decree of confiscation: “The People’s Government, aware of the mismanagement of the Foundling Home operated by the Sisters, orders them to turn the establishment over to the government, which will immediately assume the direction of this work.” Hearing that the facility was to be taken over, the children, many who never knew a home outside the orphanage, screamed and cried so loudly that the reading had to be stopped twice. “You children are not grateful to the People’s Government for assuming control of your care!” the authority scolded. A Party doctor examined the orphans. Disgusted that some of the children were ill and covered with lesions, he expressed that they were not worth the effort to save their lives, for surely they would die. One of the older orphan girls spoke out. “We would have died, too, when we came in like that, if it hadn’t been for the care of the Sisters!” she exclaimed. Lo-Sail requested of the head officer, “If you wish to assume the direction of the work, we cannot resist you. There is, however, one request we want to make: Leave us the Sisters, who have brought us up as real mothers.” “Your request is quite reasonable. The Sisters will remain with you,” the officer said. Although accused of being responsible for the deaths of babies, the devastated nuns were ordered to remain in their convent and continue with their duties until the orphanage would be officially taken over by the Communists. One of the authorities asked some of the older girls what they would do when the People’s Government would assume control. “We will work hard and keep the Foundling Home going until the Sisters return,” they answered. On the morning of March 12, 1951, three of the Sisters received permission to leave the premises, to attend Mass, but were called back as soon as they stepped outside. “Something important will happen today, so you had better remain here,” a guard told them. At 1 in the afternoon, four policemen and one policewoman from Central Bureau arrived at the mission and ordered the children to congregate in the refectory. Sensing doom, Lo-Sail ordered the children not to gather in the refectory, but rather to meet in the sewing room, next to the Sisters’ quarters, where they heard authorities order Sister Superior Saint-Alphonse-du-Rédempteur and Sister Sainte-Marie-Germaine to follow them to headquarters. “Oh, no! The Sisters are being taken from us!” cried the orphans as they ran to the nuns and clung to them as the authorities pried them off and pushed them back until the arresting party was through the exit gate, with it closed and locked behind them. But the wailing of the orphans continued as the nuns walked away. In the distance Sister Superior Saint-Alphonse-du-Rédempteur turned and defiantly waved her rosary, before one of her escorts violently shoved her along. The two women had left behind on their beds scapulars, medals, passports and money, which their consoeurs found and put away, as they packed up blankets, towels, soap and other toiletries to take to their imprisoned Sisters. The newly appointed Communist director of the orphanage stayed behind and was confronted by the orphans. “You are forever telling us that you represent the People. We are the People! We are the victims of your underhanded schemes,” cried the children. “If you don’t believe the Sisters, believe us. You despise us, because we are orphans, but the Sisters loved us and took motherly care of us! We want the Sisters! Give us the Sisters!” The director tried to assure them that the nuns would soon return, that they were merely going away for questioning. “Lies! Lies! You have taken the Sisters to prison, and we know all about it. Don’t try to fool us into believing your deceitful words. The Sisters have no bedding in prison, and they will be sick.” “The prisoners have all they need. Go back to your quarters.” The next day, March 13, at noon, again four policemen and one policewoman arrived, locked the orphans in one common room and guarded the door. In another room, the policewoman ordered three nuns to remove their rosary beads and crucifixes, as one of the policemen yelled through the closed door for them to hurry up. Pushed out of their room, the nuns were escorted through the building, as the children screamed and cried, silenced only when one of the policemen pounded threateningly on their door. And then they were gone, walking down Wai San Road to prison. The five nuns arrested over the two days were: Sister Superior Saint-Alphonse-du-Rédempteur (born Antoinette Couvrette, 1912-98, Sainte-Dorothée, County de Laval, Quebec) had been appointed superior of the orphanage four years earlier, after she arrived directly from Canada; Sister Sainte-Marie-Germaine (born Germaine Gravel, 1907-98, Saint-Prosper, County de Champlain, Quebec), the assistant superior, had arrived only months before the Communist armies. Previously, she spent 14 years in mission dispensary work in Manchuria, followed by one year in Shanghai, where she trained in pediatrics; Sister Sainte-Foy (born Élisabeth Lemire, 1909-87, Baie-du-Febvre, County de Yamaska, Quebec) had been in Canton since before the routing of the Nationalist troops that abandoned the city in anticipation of the attack and invasion by the Japanese army, in October 1939. Her first assignment was to help take care of the abandoned 730 inmates in the Municipal Insane Asylum; Sister Saint-Germain (born Imelda Laperrière, 1907-98, Pont-Rouge, County de Portneuf, Quebec) had arrived in Canton three months before the Communists “liberated” the city. Previously, she spent 12 years taking care of unwanted babies on Chung Ming Island (old form of Chongming), near Shanghai; And Sister Saint-Victor (born Germaine Tanguay, 1907-77, Acton-Vale, County de Bagot, Quebec), had arrived in Canton, in 1948, and was placed in charge of material management of the orphanage. Previously, she spent 14 years in missionary work in Soochow, Kiangsu province (old forms of Suzhou, Jiangsu). After the arrests, the Chinese People’s Relief Committee took complete physical control of the facilities, and, on March 26, the children were forced out of the orphanage to make room for authorities to move in, seemingly, the plan all along. The Canton mission of the Sisters of the Immaculate Conception was not the only one to fall victim to the Communists. In that year alone, 1951, authorities confiscated 37 Catholic orphanages throughout the mainland, after persecuting the priests and nuns who ran the facilities. As part of the program to turn the masses against the Sisters and the Church, authorities began public tours of the once-Catholic mission, guiding sightseers throughout, to show the “horrors” of the orphanage, with its walls plastered with cartoons depicting the Sisters with dead babies, as slave drivers and of beating children. The height of the exhibition was the display of bones. They had removed the slab from atop the mass grave – labeled the “death pit” – exhumed the remains of the babies and used the morbid props, sacrilegiously, for propaganda purposes. Also for propaganda purposes, the Sisters were photographed in the prison, on March 22, Maundy Thursday, with unwashed hair and in their dirty prison garb splashed with Chinese characters and their prisoners’ numbers. To publicly condemn the nuns, an accusation meeting was held at the Youth’s Cultural Hall, on March 30. With compulsory attendance, more than 1,700 gathered, including schoolchildren, military district staff, housewives, workers, medical professionals and others, all expected to verbally attack the women, in an emotionally jarring, psychological assault. Blamed for being responsible for the deaths of 2,116 babies during the 15 months following the “liberation” of Canton, the women stood, helpless, with bowed heads, without caps or veils to cover their short hair. Accusers claimed that the Sisters had plucked babies’ eyes from their sockets to make traditional Chinese medicine, which is practiced with the belief that an ailing organ or part of the body will improve if the corresponding organ or body part is eaten. Others claimed that some of the orphans had been chewed to death by rats and that swarms of mosquitoes had bitten babies because the mosquito netting had not been closed properly by the two, old, blind amahs, local nannies who helped feed the babies at night. But never did anyone mention anything about the birth mothers, those who had originally abandoned their babies, who ended up at the orphanage, either in the grave or in the crib. Returned to their cells, the Sisters secretly noticed, around the end of April, when they were let out from their cells to use the toilet, that one of the older orphans, Lick-Si Wong, was washing her face as a policeman guarded her. One evening, the guards wanted Lick-Si to go out for a bath. “The She-Devils (the nuns) are going. Would you mind accompanying them?” asked a guard. “If the She-Devils go, I don’t mind going,” said Lick-Si, hiding her happiness at the request. For 10 minutes Lick-Si and Sister Superior Saint-Alphonse-du-Rédempteur and Sister Sainte-Marie-Germaine were able to communicate. The Sisters learned that the authorities had tried to coerce Lick-Si to accuse the nuns by lying to her that they had already confessed, and that because of her unwillingness to bear false witness against the nuns, she had been arrested, on April 24, 1951. They also learned that the older orphans were sent to workhouses; that babies were still taken to the mission, but they all died; that the orphans made certain that the dying babies were baptized; that the Communists smashed to pieces the statues in the chapel and in the garden; and that the little ones respectfully buried the pieces. Before they parted, Sister Superior Saint-Alphonse-du-Rédempteur encouraged her to be faithful and to be strong in order to have truth triumph. From June 30 to September 24, the nuns were locked in 8-square-foot dungeons. The only way in or out was through a heavy door with a padlock and a small, circular peephole, through which the guards peeked every 15 minutes. In the morning, the women were let out to use the toilet. Their two meals a day, at 11 a.m. and 3:30 p.m., consisted of plain rice, with only hot water to drink. One day when the rice was served with onions, Sister Superior Saint-Alphonse-du-Rédempteur tapped on the wall and chanted, “Rice and onions! Rice and onions! This really tastes like first-class ham!” But even in the times of desolation, they sought consolation. Each Sunday morning, they sang High Mass, and in the afternoon, they sang the hymns and the “Oremus” of the Benediction of the Blessed Sacrament. Suddenly, without warning, on October 17, the women were transferred, via a Black Maria, from Lam Sek Taou to the Sail Chuen Prison, where intense brainwashing began. They were strictly forbidden to pray or to even mention the name of God. In Sister Saint-Victor’s cell, she was to memorize, with her cellmates, “Once upon a time, there was a germ. Every living organism can be explained only through evolution.” When it was her turn to repeat the sentence, she said, “You know that I am not only Catholic, but a missionary Sister. Eighteen years ago, I came to China to teach those who were still ignorant of the fact that God, the only true God, created heaven and earth and all things. You people say that man evolved from a monkey, but where did the first monkey come from?” “The monkey came from the first germ,” the teacher snapped. “But whence came the first germ?” The teacher remained silent. “This first germ came from God,” Sister Saint-Victor said, answering her own question. Jotting down beside the nun’s name, the teacher wrote: “She says that there is a God who has created all things. We tried to convince her of the contrary, but she remains ungovernable.” Later, one of the guards entered and rebuked the nun: “You must absolutely believe that evolution explains everything and that man came from a monkey.” “Believe all you want. For my part, I do not favor any monkey ancestry,” the nun replied. For two weeks in November, authorities interrogated the women, unsuccessfully badgering, taunting and ordering them to admit that God did not exist and attempting to frighten them with stories of torture performed on others who had refused to deny the existence of God. Then on Sunday, December 2, 1951, the Sisters were abruptly ordered out of their cells. They were to be tried before the People’s Court, inside the red-walled Yat-Sen Sun Memorial Hall, in front of a mob of 24,000 “judges” forced to attend. Waiting for the trial to begin, the translator tried to calm the nuns. “Do not be afraid. You will not be killed. The government only wants to give a lesson,” he said, trying to assure them, for everyone knew about the endless executions that had been carried out since the Communist takeover. Before the trial started, the mob sang rally songs, including “You Are the Lighthouse,” also known as “Follow the Communist Party”: You are the lighthouse, Shining the ocean before dawn; You are the helmsman, Holding the direction of sailing; Great Communist Party of China, You are the core, the direction; We will follow you forever, Mankind must be liberated. A signal was given. As the last notes diminished, the crowd grew silent, and the proceedings began. Prosecutor Pai-Chen Hsih screeched the indictment of their accused crimes: murder, negligence, inhuman treatment of Chinese children and the illegal sale of Chinese children. With signs strung around their necks, the nuns were herded into the circular hall, as their names and ages were broadcast over the public address system. The five looked thin and sickly. Since imprisoned, three contracted tuberculosis, and two suffered heart problems, all confirmed by a Communist nurse who examined the women after they complained that they could no longer survive on the skimpy portions of rice. Several witnesses for the prosecution stepped up to microphones set up to send the goings on of the public trial by the People throughout the city’s loudspeakers and also to broadcast live to the masses via Radio Canton. “Westerners came to China to bully us Chinese! Down with Westerners! Long live the Chinese!” someone screamed at the microphones. One of the orphans stood before the microphones. It was Tak-Po Leung. A feebleminded girl personally taken care of for eight years by Sister Sainte-Foy, who each morning lifted the girl from her bed, where she lay covered in her own filth, having eliminated during the night. Trying not to gag from the nauseating smell, the nun washed and dressed the girl. “I do it for God,” Sister Sainte-Foy told the children, who teased her about her special fondness for Tak-Po. At the microphones, Tak-Po stood, sobbing and pointing, but saying nothing. The crowd roared. After each speaker, each accuser, the audience grew more agitated, more furious. The purpose of the trial was not only to try the nuns. It was also to discredit the Church by maligning the faithful with vilification and ridicule as well as to instill fear into Catholics, to scare them into joining the Three-Self Reform Movement, the official Communist catholic church. With the women declared guilty, Judge Ze-Hsien Wen announced that the sentencing was up to the People, who, he said, were their own masters and were no longer oppressed by foreigners. For one hour, the mob screamed at the court, as individuals stood up at the microphones to order what fate should be delivered. “Hack them to pieces!” “Bury them alive!” “Lock them up!” “Kill them!” “Throw them out!” As the anger rose uncontrollably, the judge banged his gavel and intervened, “No! Do not hit them, yet!” With the mob’s frenzied deliberations quieted, the sentences were read aloud: For the superior, Sister Superior Saint-Alphonse-du-Rédempteur, and her assistant, Sister Sainte-Marie-Germaine: five years imprisonment and expulsion; For Sister Saint-Germain and Sister Saint-Victor: expulsion for life; And for Sister Sainte-Foy: a simple expulsion. After the four-hour trial, during which time the nuns had not been able to speak to defend themselves, the women were frog-marched around the circular hall, forced to bow and beg for forgiveness of their “crimes” and to thank the People for the benevolent verdicts, as the crowd roared. As the sun began to set, the five, with the signs still strung around their necks, were loaded into the back of an open-bed truck, which slowly circled in a sadistic procession outside the Memorial Hall and then crawled through the crowded streets filled with men, women and children, who spit and screamed and threw rocks at the nuns, as they headed to prison. Hit in the forehead, one of the Sisters suffered a large gash that gushed blood down her face, as she stood straight, with her head held high, eyes closed. On December 4, Sister Superior Saint-Alphonse-du-Rédempteur and Sister Sainte-Marie-Germaine were transferred to a different prison. Their consoeurs watched as the two, barely able to walk, shuffled from their cells, pulling, with difficulty, their blanket bundles. Nearly three months later, on the morning of February 25, 1952, Sister Sainte-Foy, Sister Saint-Germain and Sister Saint-Victor were abruptly informed that they were to leave China, handed their religious habits and escorted under military guard to the border. The two remaining nuns, Sister Superior Saint-Alphonse-du-Rédempteur and Sister Sainte-Marie-Germaine, stayed behind for 10 more months, eating near-starvation rations while sewing, laundering and making shoes for the Red Army 14 hours a day. Then on the Feast of the Nativity, in the afternoon of December 25, 1952, the day when light overtakes darkness, authorities told the two women that the People’s Government had benevolently pardoned their sentences and that they would be expelled the next day. Transferred to a hotel across the street from the railroad station, the two waited for deliverance. The next morning, with their religious habits returned to them, they changed from their prison rags and were escorted to the train platform, where they noticed a Chinese underground nun from their congregation, who had learned of their release. Dressed in common street clothing, she discreetly signaled a greeting. On the afternoon of December 26, 1952, the Feast of Protomartyr Saint Stephen, the nuns finally crossed Lo Wu Bridge, from a land of enslavement into a land of freedom. But they embraced their liberation with sadness, for who would care for the abandoned babies and children of China. ††† ENDNOTE: I would like to thank the Society of the Missionary Sisters of the Immaculate Conception, in Quebec, especially Sister Suzanne Labelle, for all their charitable help. Thanks also to Wen-Li “Philip” Chen, for his talents in translating Chinese to English. Miscellanea and facts for this story were pulled from the following: “Bishop Walsh of Maryknoll: Prisoner of Red China,” by Ray Kerrison; “The Bridge at Lo Wu: A Life of Sister Eamonn O’Sullivan,” by Desmond Forristal; Catholic Herald; China Missionary Bulletin; Der Spiegel; “Nun in Red China,” by Sister Mary Victoria (pen name of Sister Maria Del Rey, née Ethel Danforth); The Precursor; “Prison Memoirs,” by Sister Sainte-Foy; and “Prison Memoirs: To Kom Hang Crèche Confiscated by the Reds,” by Sister Saint-Victor. Theresa Marie Moreau is the author of “Blood of the Martyrs: Trappist Monks in Communist China,” “Misery & Virtue” and “An Unbelievable Life: 29 Years in Laogai,” which can be found online and at TheresaMarieMoreau.com. CARTOON TRANSLATION

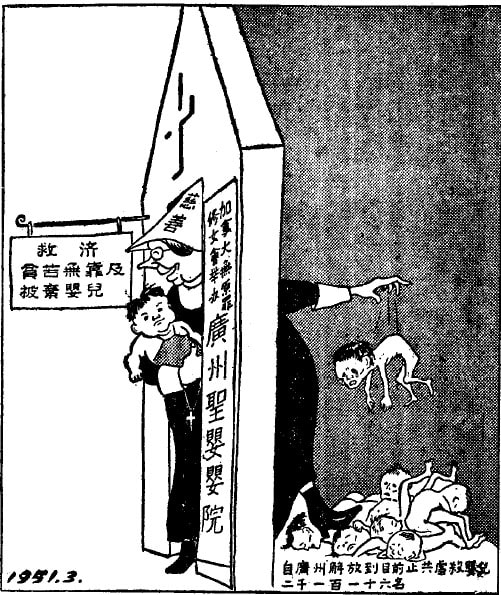

HANGING SIGN: "Relief for poor and helpless abandoned babies." NUN’S HEADPIECE: "Mercy." WALL SIGN: "The Sisters of the Immaculate Conception Society, from Canada, Holy Infant Foundling Home, of Canton." BELOW BABIES: "2,116 babies have been killed since the liberation of Canton."

5 Comments

Michel Thibeault

2/2/2019 04:54:30 pm

Thank you Theresa for bringing attention to this part of history. Sister Sainte-Marie-Germaine was my great aunt. My mother was named after her "Germaine" and as a result I inherited many stories, pictures and articles. My great aunt also wrote of book about her ordeal which I would like to make available one day. Enjoyable read and was stunned to see the propaganda cartoon for the first time. Michel

Reply

Theresa

2/6/2019 06:53:49 pm

Hi, Michel. Thanks for commenting about your great-aunt. What an amazing woman! If you ever make available her book, I would love to read it. Question for you: In a report, your great-aunt was identified as the woman on the right in the top photo. Is that correct? Thank you!

Reply

3/9/2020 05:36:46 am

China is going through a lot of things right now. I believe that we are all one in this world, so I am a believer that they are just as important as anyone else. I am not here to say that they are doing great, but they need the assistance that we can provide. I have faith that our nation can help them with whatever they are lacking off. I hope that we can provide them with all of the support that we can.

Reply

Michel

2/7/2019 06:16:39 am

Hi Theresa. Correct, the woman on the right is Sr. Germaine Gravel m.i.c. Another interesting fact is that some the infants came to the orphanage from opium addicted mothers. Addicted wet nurses would have to be found to help the child. Interesting with the backdrop of the opioid epidemic in America today.

Reply

Theresa

2/7/2019 05:47:28 pm

Hi, Michel. Wow! How interesting! I never would have thought of such a thing happening. Your great-aunt and her fellow Sisters did amazing work.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorTHERESA MARIE MOREAU is an award-winning reporter who covers Catholicism and Communism. Archives

October 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed